Chung writes:

We advocated for Measure K back in 2010 because of significant budget cuts from Sacramento. It was meant to be a temporary measure to get us through the emergency, and the tax should have expired in 2016. Instead, Measure I came along and not only did it continue the parcel tax, it increased the tax by 37%.

BIG LESSON There is no such thing as a temporary tax increase. Once a tax is introduced, there is always tremendous amount of inertia to keep it going, or even increase it.

Another thing to keep in mind is that we cannot look at individual tax in vacuum. Why? Because you have a single wallet, and from that wallet, you have to pay all the different kinds of tax, including: Federal income tax, Federal social security tax, Federal medicare tax, CA state income tax, property tax (including sub-components of parcel tax), sales tax, gas tax, etc...

10 states with the highest state income tax rates in 2018:

California: 1 to 13.3 percent

Hawaii: 1.4 to 11 percent

Oregon: 5 to 9.9 percent

Minnesota: 5.35 to 9.85 percent

Iowa: 0.36 to 8.98 percent

New Jersey: 1.4 to 8.97 percent

Vermont: 3.55 to 8.95 percent

Washington, D.C.: 4 to 8.95 percent

New York: 4 to 8.82 percent

Wisconsin: 4 to 7.65 percent

Top ten states with the highest sales tax rates in the US

10 – New York

(8.49%) – New York levies a sales tax at the state, city, and county levels. The combined sales tax rate in New York City can reach as high as 8.875%. Clothing and footwear sold for less than $110 are exempt from the tax.

9 – California

(8.56%) – The state sales tax rate in California is 7.25%, and counties, cities, and towns may charge an additional tax. Currently the highest rates in the state can be found in parts of Los Angeles, where the combined rate is 10.25%. Rate changes, if any, are published by the California Department of Tax and Fee Administration on a quarterly basis.

8 – Kansas

(8.67%) – The state sales tax rate in Kansas is 6.50%, but additional local and district taxe…

[11:14 AM, 6/29/2019] +1 (510) 754-9318: Even though at the state level, California's weighted average sales tax rate "only" ranks #9, our local sales tax rate of ~10% is among the highest in the country.

But it opened up the pandora box for parcel tax in Fremont. FUSD wanted more in 2016 and got Measure K passed with a 37% increase. Ann Crosbie is already talking about raising the tax even more next year. The current crisis is created in order to have a pretext for supporting the tax increase.

Friday, July 19, 2019

More Money for Education: What Are the Options?

https://ed100.org/lessons/moremoney

Because education funding depends heavily on income taxes paid by the top 1% of taxpayers, it tends to boom and bust with the stock market. Polls consistently show that majorities of Californians would support taxes for schools in their own community, but California's Proposition 13 makes it very difficult to pass local taxes.

Understanding the Problem

These systemic challenges are not new, and there have been many attempts to address them. They fall into four categories:

A Larger Slice. Commit more of the state budget toward education

A Bigger Pie. Raise taxes at the state level to provide more money for education

A Different Pie. Allow local taxes to provide new money for education

Actual Pie. Hold bake sales (and other local fundraisers)

Survey results consistently show that Californians can be supportive when taxes are local, and in support of local schools. Solid majorities (roughly six in ten) say they would support a local tax to support schools in their community.

In this case, the will of the majority is not enough. By passing Proposition 13, in 1978 California voters amended the California constitution to make it very difficult to pass taxes. The theory is that voters, like Odysseus, should have the power to tie themselves to the mast to resist temptation. Prop 13 requires that local governments, including school districts, must get 2/3 voter approval to pass special taxes. Prop 13 also prohibited school districts from raising property taxes based on the value of property ("ad valorem" taxes), except for issuing General Obligation Bonds for facilities.

The main available instrument for local taxation is the "parcel tax," which has been ruled permissible because it is not "ad valorem." Parcel taxes are based on the existence of a parcel of property rather than on its value. Under the rules of Prop 13, a school district can propose a parcel tax and pass it with 2/3 of votes cast. It is very difficult to get 2/3 of voters to agree to anything, but some districts manage it.

Because education funding depends heavily on income taxes paid by the top 1% of taxpayers, it tends to boom and bust with the stock market. Polls consistently show that majorities of Californians would support taxes for schools in their own community, but California's Proposition 13 makes it very difficult to pass local taxes.

Understanding the Problem

These systemic challenges are not new, and there have been many attempts to address them. They fall into four categories:

A Larger Slice. Commit more of the state budget toward education

A Bigger Pie. Raise taxes at the state level to provide more money for education

A Different Pie. Allow local taxes to provide new money for education

Actual Pie. Hold bake sales (and other local fundraisers)

Survey results consistently show that Californians can be supportive when taxes are local, and in support of local schools. Solid majorities (roughly six in ten) say they would support a local tax to support schools in their community.

In this case, the will of the majority is not enough. By passing Proposition 13, in 1978 California voters amended the California constitution to make it very difficult to pass taxes. The theory is that voters, like Odysseus, should have the power to tie themselves to the mast to resist temptation. Prop 13 requires that local governments, including school districts, must get 2/3 voter approval to pass special taxes. Prop 13 also prohibited school districts from raising property taxes based on the value of property ("ad valorem" taxes), except for issuing General Obligation Bonds for facilities.

The main available instrument for local taxation is the "parcel tax," which has been ruled permissible because it is not "ad valorem." Parcel taxes are based on the existence of a parcel of property rather than on its value. Under the rules of Prop 13, a school district can propose a parcel tax and pass it with 2/3 of votes cast. It is very difficult to get 2/3 of voters to agree to anything, but some districts manage it.

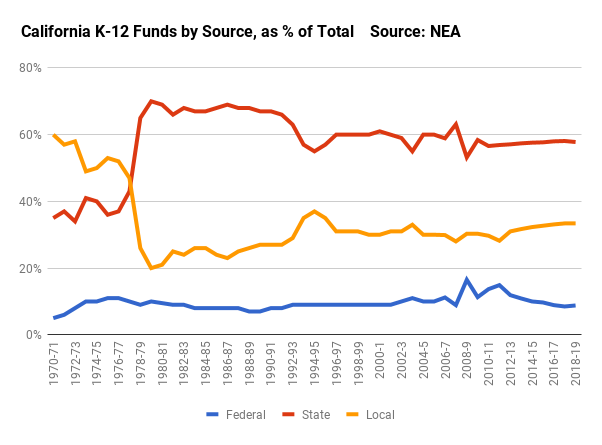

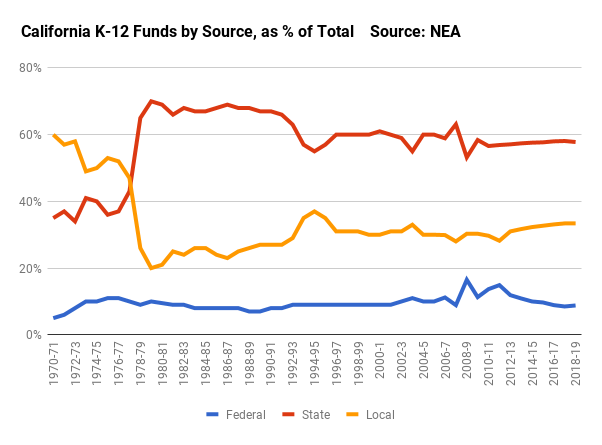

Where California's Public School Funds Come From

https://ed100.org/lessons/whopays

Property taxes are not the main source of funding for California schools, despite what people think. The biggest source is personal income taxes, especially on the state's wealthiest taxpayers.

Communities in California have very limited options for raising local revenue for schools. Other states differ in this way.

The amount per pupil your district gets is mostly driven by the rules of the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF).

Until the late 1970’s, schools in California were predominantly funded by local property taxes, as in most other states. The most basic function of a school board was to set the local property tax rate. Rates varied among districts, and receipts varied according to both the tax rate and the "assessed" (taxable) value of homes and commercial properties being taxed. Assessing the taxable value of property was an important function of county assessors.

This arrangement was great for property-rich districts, but rotten for communities with low assessed values and lots of students. Those communities had to set very high property tax rates in order to provide schools with as much money per student as their more fortunate counterparts. The Serrano v. Priest case successfully challenged this arrangement. Is it really fair, the case asked, that some districts can tax themselves at a lower level and still enjoy more funding per student than others? After all, kids have no say in the wealth of their parents. The case led to court-mandated "revenue limits," which were meant to equalize funding per student at the district level over time.

Over a period of years the state gained nearly full power over education funding. The state legislature and governor determine what portion of the budget would go to the education system, and how that portion would be distributed to local school districts. As the state became the center of power, school boards, once powerful and independent, were left with the narrower job of playing the hand dealt to them by fate and the state.

California’s skimpy funding for schools today is arguably the long-term outcome of the shift from a locally-dominated funding system to a state-dominated one. Funding for schools in 1970 required an expression of local political will in the form of a vote of the locally elected school board or a local ballot measure. Taxpayers in each community had to reach agreement to shoulder taxes on behalf of the children in their own local school district. Though politically difficult, districts could change property tax rates in response to school needs, local changes in property values, or local tolerance for taxes.

Local Schools, Centralized Funding

Today, the responsibility for funding schools falls mostly on the state. Changes in school funding largely depend on statewide political support for increasing taxes to add resources for all schools. That kind of support has proven difficult to win. Developing the necessary political will to pass a tax measure is hard even in a small town; in a state as large as California it is very hard indeed. The old system was unacceptably inequitable, but it was certainly better at raising money in total.

Property taxes are not the main source of funding for California schools, despite what people think. The biggest source is personal income taxes, especially on the state's wealthiest taxpayers.

Communities in California have very limited options for raising local revenue for schools. Other states differ in this way.

The amount per pupil your district gets is mostly driven by the rules of the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF).

Until the late 1970’s, schools in California were predominantly funded by local property taxes, as in most other states. The most basic function of a school board was to set the local property tax rate. Rates varied among districts, and receipts varied according to both the tax rate and the "assessed" (taxable) value of homes and commercial properties being taxed. Assessing the taxable value of property was an important function of county assessors.

This arrangement was great for property-rich districts, but rotten for communities with low assessed values and lots of students. Those communities had to set very high property tax rates in order to provide schools with as much money per student as their more fortunate counterparts. The Serrano v. Priest case successfully challenged this arrangement. Is it really fair, the case asked, that some districts can tax themselves at a lower level and still enjoy more funding per student than others? After all, kids have no say in the wealth of their parents. The case led to court-mandated "revenue limits," which were meant to equalize funding per student at the district level over time.

Over a period of years the state gained nearly full power over education funding. The state legislature and governor determine what portion of the budget would go to the education system, and how that portion would be distributed to local school districts. As the state became the center of power, school boards, once powerful and independent, were left with the narrower job of playing the hand dealt to them by fate and the state.

California’s skimpy funding for schools today is arguably the long-term outcome of the shift from a locally-dominated funding system to a state-dominated one. Funding for schools in 1970 required an expression of local political will in the form of a vote of the locally elected school board or a local ballot measure. Taxpayers in each community had to reach agreement to shoulder taxes on behalf of the children in their own local school district. Though politically difficult, districts could change property tax rates in response to school needs, local changes in property values, or local tolerance for taxes.

Local Schools, Centralized Funding

Today, the responsibility for funding schools falls mostly on the state. Changes in school funding largely depend on statewide political support for increasing taxes to add resources for all schools. That kind of support has proven difficult to win. Developing the necessary political will to pass a tax measure is hard even in a small town; in a state as large as California it is very hard indeed. The old system was unacceptably inequitable, but it was certainly better at raising money in total.

California’s school funding flaws

https://edsource.org/2019/californias-school-funding-flaws-make-it-more-difficult-for-districts-to-meet-teacher-demands/608824

Oakland is not the only district that is looking for more assistance from Sacramento. Despite Los Angeles teachers reaching an agreement with the district after a week-long strike, it is hard to imagine how Los Angeles Unified will be able to make good on what it promised at the bargaining table without additional support from the state.

A report as sobering as the Oakland fact-finding report came from L.A. County Superintendent of Schools Debra Duardo after examining the agreement with United Teachers LA.

The agreement, she implied, has put the district at financial risk. “Using one-time funding sources, such as reserves, to cover ongoing salary expenditures is a key indicator of risk for potential insolvency,” she reported in her report, also required by state law.

She pointed out that L.A. Unified is projecting a deficit of over $500 million in three years, “which has yet to be addressed.” Unless the district does so, she threatened to label the district as no longer being a “going concern,” the dreaded accounting term indicating that an organization or business does not have the resources to keep operating in the foreseeable future.

Oakland is not the only district that is looking for more assistance from Sacramento. Despite Los Angeles teachers reaching an agreement with the district after a week-long strike, it is hard to imagine how Los Angeles Unified will be able to make good on what it promised at the bargaining table without additional support from the state.

A report as sobering as the Oakland fact-finding report came from L.A. County Superintendent of Schools Debra Duardo after examining the agreement with United Teachers LA.

The agreement, she implied, has put the district at financial risk. “Using one-time funding sources, such as reserves, to cover ongoing salary expenditures is a key indicator of risk for potential insolvency,” she reported in her report, also required by state law.

She pointed out that L.A. Unified is projecting a deficit of over $500 million in three years, “which has yet to be addressed.” Unless the district does so, she threatened to label the district as no longer being a “going concern,” the dreaded accounting term indicating that an organization or business does not have the resources to keep operating in the foreseeable future.

What Are “Basic Aid” Districts?

Almost all districts in the state get their basic funding from property taxes plus additional support from the state, typically around $5,000 per student. This amount is known as “revenue limit” funding.

However, 127 “basic aid” districts, usually in communities with high-value property, generate more of their basic funding from property taxes than the total “revenue limit” funding they would normally get from the state.

Under regulations established decades ago, they are allowed to spend these “excess” property tax funds on their students, without being bound by state revenue limits.

However, not all basic aid districts serve an affluent student population. As a result of the state’s budget crisis, the number of basic aid school districts has grown in recent years because the amount they are eligible to receive through revenue limit funding has dropped below the amount they are able to generate entirely from their property taxes.

But in general, research shows that the existence of basic aid districts has helped sustain the disparities in funding among California school districts.

However, 127 “basic aid” districts, usually in communities with high-value property, generate more of their basic funding from property taxes than the total “revenue limit” funding they would normally get from the state.

Under regulations established decades ago, they are allowed to spend these “excess” property tax funds on their students, without being bound by state revenue limits.

However, not all basic aid districts serve an affluent student population. As a result of the state’s budget crisis, the number of basic aid school districts has grown in recent years because the amount they are eligible to receive through revenue limit funding has dropped below the amount they are able to generate entirely from their property taxes.

But in general, research shows that the existence of basic aid districts has helped sustain the disparities in funding among California school districts.

Parcel Taxes 190719

"Personally I would be ok with a $378 annual parcel tax"

Sure, it started out as just $53, went up to $73, now $378?

How high can it go?

San Carlos Education Foundation asks for $1500 per child every year.

That would be $3000 per year if you have two kids in school.

ballotpedia says:

In 2013, all FUSD employees including all administrators received an one-time 4% (relative to their salaries) payment and a 2% salary raise retroactive back to 2012. In 2014, all employees received a 5.9% salary increase. In 2015, the salary increase is 5%. There is another salary negotiation underway this year for the 4th consecutive year. Measure I money would be used to mostly offset routine and normal FUSD expenses.

https://edsource.org/2019/voters-in-la-soundly-reject-parcel-tax-for-schools/613344

Setting back efforts to restore Los Angeles Unified to financial health, voters have decisively rejected a tax on real estate which would have raised approximately $500 million annually for the state’s largest school district.

With 100 percent of precincts reporting at 1 a.m. Wednesday, Measure EE won only 45.68 percent of the vote, with 54.32 percent against. That was more than 20 percentage points less than the two-thirds majority the parcel tax measure needed for passage.

The measure, which would have been in effect for 12 years, would have imposed a tax of 16 cents per square foot of interior space on residential and commercial property. The owner of a 2,000 square-foot-house would have paid $320 a year.

The overwhelming defeat of the measure represents a major setback to teachers and many other backers of the measure, including the Los Angeles school board and Mayor Eric Garcetti. The board voted unanimously in February to put Measure EE on the ballot in the wake of a teachers’ strike that attracted significant public support. The board commissioned a survey earlier this year that showed that more than two-thirds of respondents said they would support a 16 cents per square foot parcel tax.

“Yesterday, Los Angeles voters showed us they want absolute accountability and oversight when asked to approve impactful tax increases like Measure EE,” said Maria Salinas, president and CEO of the Los Angeles Area Chamber of Commerce.

The anti-measure statement in the ballot read in part: “DON’T BE FOOLED. Money from the tax won’t add resources to classrooms. It will be used to temporarily fix a budget deficit and to pay for LAUSD’s over-promised pension and health insurance costs.”

Tuesday’s vote marked the second time since 2010 that the district had failed to pass a parcel tax. The 2010 measure received less than 53 percent of voter support.

https://mk0edsource0y23p672y.kinstacdn.com/wp-content/publications/pub13-ParcelTaxesFinal.pdf

Despite sustained efforts to reduce unequal revenues among California school districts, inequities remain for a variety of reasons, including differences in revenues generated from federal programs and local fundraising efforts.

One pitfall of the potentially greater usage of the parcel tax is that it could exacerbate these inequities.

Districts taking advantage of parcel taxes are overwhelmingly based in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Nearly half of all districts with parcel taxes are in just three Bay Area counties (Santa Clara, San Mateo, and Marin).

More than one-third of districts with parcel taxes are “basic aid” districts, which are among the wealthier school districts in the state.

Parcel taxes typically generate a small percentage of total spending in school districts that have parcel taxes (an average of 6%).

Sure, it started out as just $53, went up to $73, now $378?

How high can it go?

San Carlos Education Foundation asks for $1500 per child every year.

That would be $3000 per year if you have two kids in school.

ballotpedia says:

In 2013, all FUSD employees including all administrators received an one-time 4% (relative to their salaries) payment and a 2% salary raise retroactive back to 2012. In 2014, all employees received a 5.9% salary increase. In 2015, the salary increase is 5%. There is another salary negotiation underway this year for the 4th consecutive year. Measure I money would be used to mostly offset routine and normal FUSD expenses.

https://edsource.org/2019/voters-in-la-soundly-reject-parcel-tax-for-schools/613344

Setting back efforts to restore Los Angeles Unified to financial health, voters have decisively rejected a tax on real estate which would have raised approximately $500 million annually for the state’s largest school district.

With 100 percent of precincts reporting at 1 a.m. Wednesday, Measure EE won only 45.68 percent of the vote, with 54.32 percent against. That was more than 20 percentage points less than the two-thirds majority the parcel tax measure needed for passage.

The measure, which would have been in effect for 12 years, would have imposed a tax of 16 cents per square foot of interior space on residential and commercial property. The owner of a 2,000 square-foot-house would have paid $320 a year.

The overwhelming defeat of the measure represents a major setback to teachers and many other backers of the measure, including the Los Angeles school board and Mayor Eric Garcetti. The board voted unanimously in February to put Measure EE on the ballot in the wake of a teachers’ strike that attracted significant public support. The board commissioned a survey earlier this year that showed that more than two-thirds of respondents said they would support a 16 cents per square foot parcel tax.

“Yesterday, Los Angeles voters showed us they want absolute accountability and oversight when asked to approve impactful tax increases like Measure EE,” said Maria Salinas, president and CEO of the Los Angeles Area Chamber of Commerce.

The anti-measure statement in the ballot read in part: “DON’T BE FOOLED. Money from the tax won’t add resources to classrooms. It will be used to temporarily fix a budget deficit and to pay for LAUSD’s over-promised pension and health insurance costs.”

Tuesday’s vote marked the second time since 2010 that the district had failed to pass a parcel tax. The 2010 measure received less than 53 percent of voter support.

https://mk0edsource0y23p672y.kinstacdn.com/wp-content/publications/pub13-ParcelTaxesFinal.pdf

Despite sustained efforts to reduce unequal revenues among California school districts, inequities remain for a variety of reasons, including differences in revenues generated from federal programs and local fundraising efforts.

One pitfall of the potentially greater usage of the parcel tax is that it could exacerbate these inequities.

Districts taking advantage of parcel taxes are overwhelmingly based in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Nearly half of all districts with parcel taxes are in just three Bay Area counties (Santa Clara, San Mateo, and Marin).

More than one-third of districts with parcel taxes are “basic aid” districts, which are among the wealthier school districts in the state.

Parcel taxes typically generate a small percentage of total spending in school districts that have parcel taxes (an average of 6%).

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)